|

|

Pvt. James Baldwin

Company D by John Cameron As in other northern states, many of Wisconsin's young men responded with great enthusiasm to the initial call to arms. Local militia was organized spontaneously and funds raised voluntarily to clothe and arm the boys as they marched off to anticipated glory in the spring of 1861. A year later, with one-year stints expiring and a string of demoralizing defeats hampering reenlistment efforts, President Lincoln called for additional state levies of men to restore the depleted Union ranks. States that failed to recruit their quota by September, 1862 were required to institute a draft. Again the leading citizens of Wisconsin towns organized patriotic rallies designed to recreate the revival-like fever in support of the war and encourage the initially hesitant to sign up. At one such affair in Whitewater that August, recently commissioned Captain Edward S. Redington raised another company for the Wisconsin infantry. Enlisting in the new unit was the 33-year-old widower James Baldwin. Before he left for Camp Washburn in Milwaukee, James married a second time. His new wife Harriet would look after his eight-year-old daughter. Captain Redington's volunteers were designated Company D of the 28th Regiment of the Wisconsin Infantry when it was formally organized on September 13, 1862. Most of the new regiment was drawn from the southeastern counties of Waukesha and Walworth, although a number who joined up came from neighboring townships in Jefferson County. James officially was mustered in a month later. Army records note that he was 5' 8" tall, of medium build with blue eyes, brown hair and fair complexion. His occupation was designated as "carpenter." James had enlisted as private for the standard three-year period and received a $25 bonus payment.

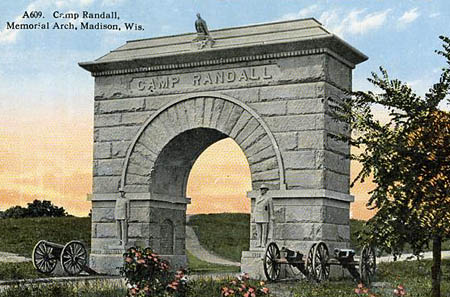

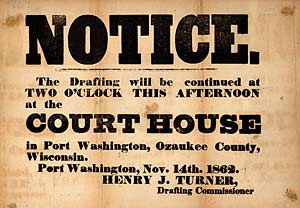

Although thousands of other Wisconsin men had also volunteered in those weeks, the state still fell short of its quota and had instituted a conscription system. It was not well received by all, particularly among the state's many European immigrants. The first assignment for the new companies of the 28th Regiment was a 30-mile trip to Port Washington in Ozaukee County to quell the anti-draft disturbances in that heavily German and Belgian community along Lake Michigan. The regiment did not leave Wisconsin until late December, when it traveled down the Illinois Central rail line to Cairo, then by steamer to Columbus, Kentucky. On Christmas Day its troops were sent on a raid to destroy rebel supplies in nearby Hickman that met little resistance. Shortly after the New Year in 1863 the regiment again entrained to Memphis, and then traveled by steamer to the Mississippi River town of Helena, Arkansas, where it was stationed as part of the 2nd Brigade of the 13th Division of the 13th Army Corps. In the following weeks the regiment took part in an expedition through eastern Arkansas to the White River, securing the towns of Des Arc and Duvall's Bluff, before returning to Helena on January 23. A month later the regiment joined General Grant's attempt to move on Vicksburg through the Yazoo Pass. Union troops chopped away through the dense "delta" lands of northwestern Mississippi, connecting the big river by canal to Moon Lake, then through the Yazoo Pass to the Coldwater and Tallahatchie Rivers. The latter ran into the Yazoo River that led to Vicksburg from the northeast. By mid-March Grant's men had reached the juncture of the Tallahatchie and Yalabusha Rivers, which was strongly guarded by Fort Pemberton. Despite a prolonged bombardment and land assault in which the 28th Wisconsin participated, federal forces could not silence the fort or proceed further down the river. Early the next month they returned to camp in Helena, which they then helped fortify. With her husband away, Harriet Baldwin had gone to help cook at Camp Randall, a major training ground for Wisconsin troops in Madison. Pumping water and the other heavy labor involved strained her health, and she died there in May. On receiving the news in early June, James was granted a 30-day furlough to return home and settle his affairs. It was arranged for Mrs. Parks, Harriet's sister, to take over the care of Junietta.

While James was still on furlough, the 28th Regiment fought its most ferocious battle of the war. The Wisconsin men were among the 4000 federal troops encamped at strongly fortified Helena that were assaulted by nearly twice that number of Arkansas and Missouri Confederates on the Fourth of July. The rebel attack at Helena was designed to relieve Union pressure on besieged Vicksburg. The southern troops failed to take the several batteries defending the town and sustained an estimated 1000 casualties before withdrawing. That same day the Confederate defenders of Vicksburg surrendered at last to General Grant, while Lee's forces began retreating through the rain from their decisive defeat at Gettysburg. Edward Redington's letters to his wife describing the battle of Helena along with dozens of others he wrote her in 1863 survived to be transcribed and typed up as part of a Works Progress Administration project three-quarters of a century later. Now on file at the state archives in Madison, they provide a firsthand account of the experiences shared by James in those months, as well as a few lines about him personally. Like most soldiers writing home, Captain Redington's letters are filled with a mixture of homesickness, gripes about bad food, observations about the weather and descriptions of new sights seen. As an officer, he was also much concerned with the personalities of the men he led, their varying degrees of ill-health, comments on the war in general and on regimental politics in particular (politics played a big role in the volunteer state forces.) In letters before the assault on Helena, Redington frequently complained about the lack of action, writing that "I rather have three fights a week and do not believe there would be half as many lost as are dying deaths on this miserable muddy bottom" and that "I had a thousand times rather face all the rebels in the South than a charge from this terrible typhoid fever." On the skirmish before Fort Pemberton, he noted that they arrived "too late to see the fun for the day" and bemoaned that "where the 28th goes there is sure to be no fighting." At Helena he had a glimpse of the industrialized carnage that characterized so many of the larger engagements of the war and his tone changed dramatically. To his wife three days later he wrote, "I will not attempt to describe the horrors of the battlefield...after the excitement was over, I walked over the field, and O what a sight. God forbid that I ever see another. I will not say more about it, the thought is bad enough." Another set of changing attitudes illustrated in his correspondence of that year was Edward's views on blacks and slavery. On first arriving in the South he perceived African-American as an exotic, if clearly inferior species. He early on sent an "Ethiopian girl" back to Whitewater to work for his wife, strictly admonishing her that she "must not make an equal of them, they will not bear it...we treat them fairly but keep them at arms length." As the months progressed and he became more acquainted with the social order of the slave economy, he was more appreciative of the capabilities of blacks, no longer dismissing them as "lazy scamps" but writing that "Negroes are best by far for soldiers in this country." As the former slaves, freed under the terms of the Emancipation Proclamation, flocked by the thousands to Union lines, Redington also developed real sympathy for their plight and a much harsher view of the "Infernal Institution of slavery" calling it a "curse" and "hideous deformity" of the South. Eventually he gave serious consideration to applying for an officer post in one of the newly raised all-black regiments. His sympathy for my great-great grandfather, on the other hand, was strained. On June 6, 1863 he wrote of obtaining a furlough for "some of the boys. One is James Baldwin" and two days later of sending "a little box by Baldwin" for his daughter. On July 12 however, Redington was less than pleased with James who was almost a week late returning from Wisconsin, telling his wife "That sneak of a Baldwin has not come yet. I have written to Graham today to arrest him as a deserter. He is not only making himself liable to severe penalties, but is keeping others from coming home." By his own admission, the captain was ill and out-of-sorts when he wrote those lines, and there is no subsequent mention of matter in future letters. The military records submitted by Redington contain no reprimand and James is listed as present and paid at the July-August muster, so it's not clear just how it was resolved. James always referred to Redington, who he would serve under for the rest of the war, with the greatest of respect. A month after the victory at Helena, General Frederick Steele led a federal march on Little Rock. The 28th Wisconsin was among the 12,000 troops that routed a rebel counterassault along the Arkansas River before occupying the abandoned Confederate capitol on September 10. The regiment remained in Little Rock throughout the fall of 1863 except for a brief sortie against Mt. Elba. In early November James was detached with others from his company under Captain Redington and detailed to the Pioneer Corps of the 3rd Division of the Army of the Arkansas. While the rest of the regiment removed to Pine Bluff, which it would garrison for more than a year, Redington's pioneers remained in Little Rock. The Pioneer Corps were the army's engineers. No doubt James Baldwin's trade as a carpenter was useful in building the roads, bridges and fortifications that were so central to military tactics of the Civil War. In wasn't until March, 1865 that James was returned to regular duty, rejoining Company D the following month. By then his regiment was reassigned to the 13th Army Corps. Under the command of General Gordon Granger, 45,000 men had been transported down the White River to the Mississippi, then on to New Orleans and from there along the Gulf Coast to join a three-pronged attack on Mobile, Alabama. The 28th Wisconsin took part in the assault on Spanish Fort, a major Confederate stronghold on the east side of Mobile Bay. After a 13-day siege, the Union troops captured the work on April 8, and the next day the federals overran Fort Blakely to its north, capturing its entire garrison of several thousand defenders. Three days later the remaining 5,000 rebel troops evacuated Mobile, retreating up the Tombigbee River, with federal forces in pursuit for several weeks. By then Lincoln had been assassinated and Lee had surrendered at Appomattox Court House, followed shortly by Johnston's surrender near Raleigh, North Carolina. At the end of May James' regiment embarked on transports for Brazos Santiago, Texas at the mouth of the Rio Grande, arriving on June 6. A few weeks earlier the last battle of the Civil War had been fought at nearby Palmito Ranch, leading to the surrender on May 26 of General Kirby Smith's trans-Mississippi Confederates and the end of the war. The 28th Regiment moved on to Clarksville, Texas ten days later and remained on picket duty through early August. It then marched to Brownsville, where the regiment was mustered out on August 23. The muster out roll stated that James Baldwin had last been paid in February and was due $75 in bonus payments, while also noting that he had drawn $46.86 out of his clothing account and had been docked $6 for a musket and "accouterments" that he kept. By the middle of the next month the regiment had returned to Wisconsin, almost three years to the day after it had been organized, and it was formally disbanded at Madison on September 23, 1865.

Originally written and titled "Grandpa Baldwin & the Civil War" in 2003, this story was generously shared by author and descendant John Cameron.

| ||

|

Last Updated:

Webmaster: |